How do students create such amazing artworks? The process of artmaking and the benchmark for success

To provide a window into some of the engaging and innovative teaching and learning happening in our classrooms across the College, our Head of Learning Area – Visual Arts, Ms Brigiat Maltese, shares her thoughts on the process of artmaking and assessment.

‘How do those students create such amazing works?’ seems an apt alternate title for this piece as there is sometimes a sense of mystery about how students create skillfully resolved and conceptually rich artworks. Is it due to an innate ‘talent’? Does that mean Visual Arts is available to some but not others? Can creativity be taught? The ability for students to create artworks aligns to the teaching of critical and creative thinking and, yes, these are skills than can be taught, developed, and refined. It is for this reason that the Visual Arts classroom is for all students as they develop transferable skills; making artworks that reflect acting on ideas (1)

It is the uniqueness of Visual Arts practices and the learning associated with artmaking that is particularly relevant in the development of 21st-century skills (also known as Global Competencies). These skills are identified as those particularly relevant as the world moves into information-rich and relational-based interactions. These interactions are ever present in the Visual Arts classroom as the fluid interaction between teacher and student in a cycle of feedback is especially important. An ability to a capacity to respond in a well-prepared yet flexible manner is what ultimately leads to deep learning in the Visual Arts. The challenge for teachers is to balance a series of learning outcomes, a focus on big questions, alongside a prepared program which creates space for student discoveries and conversations that occur within the classroom. It is the finesse of the expert Visual Arts educator; balancing these nuanced elements that are a significant determining factor in terms of student artmaking success.

John Hattie’s research recognises the power of the teacher and goes a step further in “ascertaining the attributes of excellence”(3). He explores the dimensions of an expert as opposed to experienced teachers. His views resonate with my observations of high performing Visual Arts educators at Pymble as these teachers successfully respond/operate/facilitate/inspire within a learning environment that is characterised by what Hattie has termed, “real fluid time interaction”(2). What a perfect way to describe the interactions that take place in an ‘artmaking’ classroom. What interests me here is the specific attributes associated with expert Visual Arts teachers, especially within the area of artmaking.

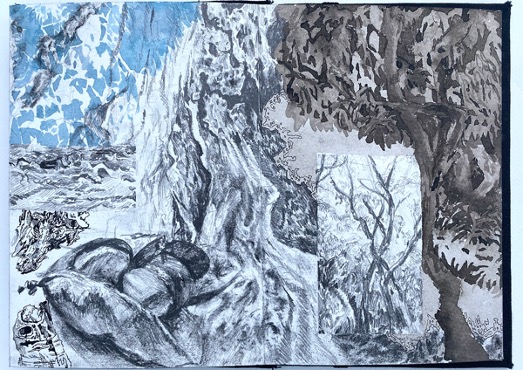

In terms of artmaking practice, the Visual Arts classroom is a dynamic place that is characterised by processes that can sometimes occur at a rapid pace, within “a network of procedures”(2) that are organic and circular in manner. It is beneficial for students (and teachers) to explicitly identify and be informed by these processes. In this way students ‘work through’ the creation of an artwork, focusing on informed choices and thoughtful actions. Where necessary, the expert teacher will slow down or speed up these processes related to artmaking, according to the needs of the class or individual. One way of doing this is the use of use of benchmark work samples and teacher demonstrations. In other words, explicitly show and describe successful artmaking.

Artmaking units of work are designed to maximise learning and success, that’s a given but what does ‘success’ look like – expert Visual Arts teachers know the outcome of each unit (through past experience) and will often create and use ‘work samples’ as exemplars. Successful past student samples show current students what ‘excellent’ looks like. This is also an approach used by our expert teachers. High benchmark examples in terms of artworks are used not to limit innovation but rather to inform and enlighten potential approaches, these works become real life examples of the specific qualities evident in successful artworks. These benchmarks also open up the whole conversation of what is good and what is not. This philosophical debate is one that all students can have. It enables them to also explore bigger issues like; What is art? Who decides what is good or aesthetic? What role does the artists’ intention play?

Visual Arts by its very nature is subject to a kind of popular psychology that sees art as a highly subjective and emotive activity. In terms of this view, Art activities for students are valued in terms of how it makes them feel. Students often adopt this framework too. It often sounds like, “I like my work and want it to look this way and I think it looks good”. An expert teacher opens up this conversation and can explain that artworks should not be judged as ‘good’ or ‘bad’ or even ‘excellent’ because it is deemed to be such. If an artwork were valued according to an “I like it” framework, there is little that needs to be taught and nothing to assess. It is important for students to explicitly understand that artmaking practice occurs within conventions, contexts and parameters. Certain skills are developed and refined; ideas are explored. Students need to clearly understand the context of their own artmaking; work samples/benchmarks are a good way of explaining this. The capacity for students to make judgements and discriminate is pertinent in all Stages of the Visual Arts continuum. This explicit approach to seeing and explaining excellence creates skills that are particularly important in Stage 6 Visual Arts because it is at this point those students make increasingly autonomous decisions about their own work, culminating in the creation of a self-directed and independent ‘Body of Work’.

Another way to enhance student skills in development of informed judgements is to provide benchmarks created by other artists. The more experiences students have of the art world, artists and works the richer their own reference points and the more diverse their understanding of what is excellent. Here the teacher is instrumental in communicating about the values inherent in these artists’ works. It is not about copying but rather possibilities. The expert teacher becomes the conduit between the art world and the specifics of the values in the syllabus. Not all artists are appropriate for students learning (for a whole range of reasons) and the expert Visual Arts teacher will know which kinds of works/artists to use as a part of the development of artmaking practice. The more direct and in-depth the experience with these artists the richer the student experience and the greater the level of student engagement. The phrase I have used with students in order to help them understand the role of artists is ‘The

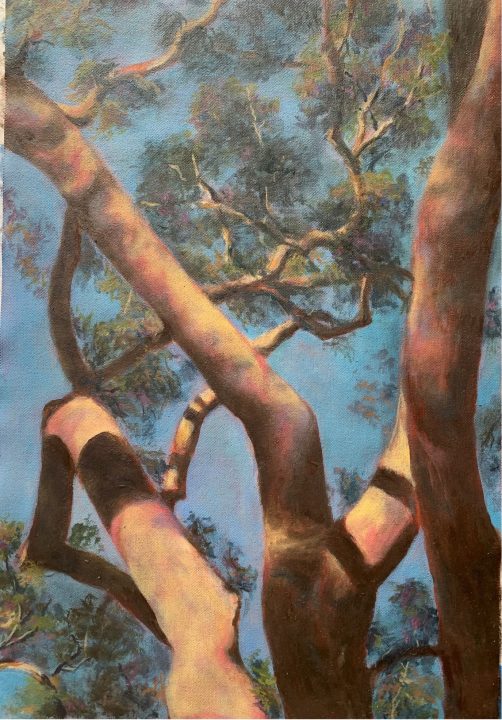

Artist as Mentor’. It is the teacher who brings these mentors to students and as students develop autonomy, they then acquire the skills to locate their own ‘mentor’ according to a set of criteria and intentions. Rather than selecting artists and artworks based on “I really like this work”. This became particularly evident when Year 11 Visual Arts students visited Vision Valley as part of the two-day Art Camp and worked with both expert teachers and the artist Patrick Shirvington.

The Year 11 Visual Arts course becomes a crucial ‘Context Bound’ nursery. Hattie also recognises that expert teachers are awareness of “existing contexts”(2). The use of an ‘Artist as Mentor’ is valuable in the Preliminary Course as it provides the framework for enquiry-based deep learning rather than the importing information. In the HSC year, students in consultation with their expert teacher also create their own benchmarks of ‘excellent’ through the selection of Artists as Mentors. Viewing exhibitions is also another way to support the ‘Artist as Mentor’ approach. The expert teacher guides the enquiry posing such questions as, “What is excellent and why?” It is the explicit demystifying of the qualities associated with a high standard of work and conversely an explanation of the qualities of an average or limited work that makes the difference. Students are enabled and challenged to reflect and make informed choices about their own artmaking. In conjunction to this, students develop a language to explain the ‘why’ and ‘how’ about their own artmaking.

Within Visual Arts, learning is visible in the art made by students. This culminates at the end of Stage 6 where students create a fully resolved, self-directed Body of Work. By its very nature, this work in a unique thing and is the result of “student questioning”1 and the informed ‘working through’ of a creative process. Ultimately it should show evidence of a high degree of sophistication in terms of materials and concept. This excellence does not occur by accident or by a subjective “I know what I like” approach. Excellence within the Visual Arts is the result of deep student engagement and expert teaching and all that this entails. A passionate ‘expert’ Visual Arts teacher is one who is “clear about learning intentions”(4) and makes the “success criteria absolutely obvious” (4). What does this look like in a Visual Arts classroom? It is a classroom that challenges students, enables them to value the creative process, makes tangible connections to the art world, engages students in critical dialogue and develops informed judgments all within a well-crafted, well-resourced learning context. It is a place with tangible benchmarks (artworks) and the language to explain these in a clear manner. It is also a place where experimentation is valued; mistakes are seen as a way through and other artists as well as teachers are used as mentors. Is it any wonder that truly amazing artworks can and do happen?

References

- Quinn, McEachen, Fullan, Gardner and Drummy (2020) Dive Into Deep Learning, Corwin

- Hattie, John (2003, October). Teachers Make a Difference. What is the research

evidence? University of Auckland, Australian Council for Educational Research - NESA Stage 6 Visual Arts Syllabus

- Stevenson, Andrew (June 10, 2011) Just shut up and listen, expert tells teachers.

Sydney Morning Herald - visiblelearning.co.nz

- hattie@auckland.ac.nz www.education.auckland.ac.nz/staff/j.hattie/