Women Kickstarting a Sporting Revolution

Buoyed by progress in 2023, a year that witnessed many firsts, women are pushing new boundaries in Australian sport and making the whole world sit up and take notice.

By Melinda Ham

ALICE TARNAWSKI, 29, a part-time professional sailor, exemplifies the determination of an athlete breaking barriers for women in sport.

In 2022, she and co-skipper Clare Constanzo were rescued after 14 hours adrift on the hull of a racing yacht. They had capsized at night while on a qualifying passage for the two-handed category in that year’s Sydney to Hobart.

Undeterred, Tarnawski took on the 2023 race in the high-pressure role as navigator on URM Group, the only woman among 21 crew on the 72-foot Maxi that finished second overall. The winning yacht, Alive, had a woman navigator too, Adrienne Cahalan, a pioneering Australian yachtswoman. The race had a record number of nine female skippers.

Offshore sailing may be having its moment. For the first time in its 173-year history, this year’s America’s Cup Challenge – the oldest international sports contest still running – will have a women’s competition.

Australia’s team includes Olympian Nina Curtis.

Women such as Nina have long been

ALICE TARNAWSKI, PROFESSIONAL SAILOR

role models for us all … showing there’s

a pathway to reach your goal.

“Women such as Nina have long been role models for us all, and the younger girls, showing there’s a pathway to reach your goal,” says Tarnawski.

Across Australia, athletes, coaches and sports administrators are challenging age-old tropes about women’s participation in sport. The Matildas’ World Cup soccer success – the first time a senior men’s or women’s team has made it into the semi-finals – shook up the perception of women and girls’ involvement in sport, says Professor Clare Hanlon, Susan Alberti Women in Sport Chair at Victoria University.

“It had a profound effect, and many commentators say it has created generational change for women in sports,” says Hanlon. “Of course, the women players were amazing and that’s certainly worth celebrating. But, off field, TV viewing records were smashed, games were sold out across the country and more Matildas jerseys were sold before the Women’s World Cup began than the Socceroos during and after the Men’s World Cup in Qatar.”

Living the Dream

Younger soccer players, such as 20-year-old Sarah Hunter, pictured at left, are now living the dream. After making her debut with the Matilda’s senior team in December last year, she’s currently being considered for the Olympics. In the meantime, she’s signed a three-year contract with Paris FC Division 1 having played a year with Western Sydney Wanderers and Sydney FC.

“It’s been a really crazy experience,” says Hunter, a graduate of Pymble Ladies’ College and now part way through an exercise science degree at the University of Sydney. “We played in a champions league, the top league for all the teams in Europe. So, we just played Chelsea, Real Madrid, Arsenal – all these really big teams.”

As a long-time Chelsea fan before she became a professional, her most exciting moment so far was playing at the famous club’s home ground at Stamford Bridge Stadium, London. “It was a total dream to play there.”

Hunter says she hopes that the Matildas’ success will have a ripple effect across sports – from the grassroots up.

“It’s changing the funding for junior programs and development squads, and that goes through all levels. Having the women players to look up to is getting a lot of girls interested and that affects the sport’s future growth.”

Can – and do – inspire change

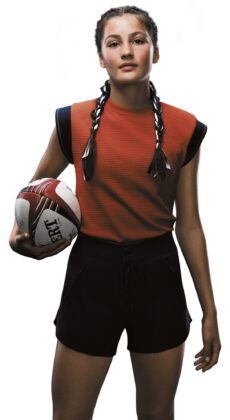

Chloe Dalton, 30, pictured at right, started out playing rugby in her backyard with her brothers but never imagined she’d be standing on a podium with her team winning gold in the women’s Rugby 7s at the 2016 Rio Olympics.

In the year running up to the Games she’d fractured her arm three times. With the help of a 12-centimetre pin and nine screws she was able to play. Her team’s Olympic gold was an inspiration for girls playing rugby across Australia.

“The gold ignited an incredible flow-on effect in participation numbers in young girls starting to play rugby after that,” says Dalton. “I got so many messages and emails from parents who’d held their kids back from school because the game was on at school starting time, and they all wanted to watch us.”

Dalton, also a Pymble alumna, is one of those inspiring athletes who has played at the elite level in not one, but three sports.

She started off playing basketball for the Sydney Uni Flames in the Women’s National Basketball League and then Rugby 7s at the Rio Olympics, before then switching to AFLW, playing first for Carlton and currently as a medium defender for the Greater Western Sydney Giants.

While high-profile individual athletes can and do inspire change, the momentum in sport for women and girls comes from players who have a vision to drive change in the less glamorous business of making sport work for women – taking on issues such as pay equity, age-old uniform rules, lack of facilities, and strengthening networks and governance.

Take Laura Kane, the first female executive general manager of football at the Australian Football League (AFL), appointed in August 2023. She’s also one of the highest-ranking women in a leadership position across any football code. Kane took on the role having been a player and coach.

You need to shift the culture of any organisation.

LAURA KANE, EXECUTIVE GENERAL MANAGER, AFL

This only happens when the board table or the

meeting room represents the community …

“You need to shift the culture of any organisation,” she says. “This only happens when the board table or the meeting room represents the community, it’s diverse and it represents a whole different set of views – and it gets women in leadership roles in sport who can then make decisions.”

Driven by vision

Kane has always been driven by a larger vision. When there weren’t any Australian Rules teams available for teenage girls to play anywhere in Melbourne – back in the early 2000s – she formed one with her school friends.

“One day, I was walking home from school when I was about 12 and I saw these women training and playing AFL,” she recalls. “I ran all the way home and screamed to my mum: ‘There were women playing footy!’” This was the University of Melbourne’s women’s team and Kane and her mother went back to the oval and asked if she could train with them.

One day, I was walking home from school when

LAURA KANE, EXECUTIVE GENERAL MANAGER, AFL

I was about 12 and I saw these women training and playing AFL. I ran all the way home and screamed to my mum: ‘There were women playing footy!’”

Since she was four years old, Kane had played in boys’ teams but once she’d reached year 6, this was no longer allowed, a typical experience for many. For the next three years, Kane trained with the university squad but couldn’t play games because she was too young for senior women’s football and there was no youth league.

So, in year 10, Kane called up all of her friends – about 20 girls – and formed a team for the first Youth Girls League, an under-18 AFL girls’ competition held in 2004. The AFL’s women’s league, the AFLW, didn’t launch until 2017 but today has women’s teams representing each of the original 18 AFL clubs.

Focusing attention on women in sport is critical, too, especially when mainstream media coverage is lagging. Dalton launched her own weekly sports podcast, the [Female] Athlete Project, to address the visibility issue that persists today. With more than 120,000 followers, the podcast celebrates women athletes across all manner of sports, such as rock climbing, boxing or surfing (and, of course, football) accompanied by an active social media presence.

Pay and prize parity

Equity with men’s competitions in terms of financial reward is also important. Collective bargaining agreements (CBAs) struck in a range of domestic codes in 2023 began to tackle issues such as minimum salaries, working conditions, travel arrangements and a medium-term plan to get women athletes to become full-time professionals.

“This is so important because it allows female athletes to focus solely on what they need to do to perform and compete at their best,” Dalton says.

Regardless of gender, Australian cricketers receive the same base pay rate, under the current memorandum of understanding agreed with the Australian Cricketers’ Association in 2017.

Prize-money parity is also improving. Tennis Australia and Cricket Australia have had gender parity for years. In tennis, prize money is equal across all Grand Slam tournaments. The Australian Open first awarded equal prize money in 1984, and all four slams were doing so by 2007. In cricket, the men’s and women’s Big Bash tournaments have offered equal prize money since the 2017- 18 season.

The AFL introduced prize money parity in 2023, while the NSW government this year requires all sporting peak bodies to provide a plan for equal prize money when they apply for funding.

Designing for women

Making sport welcoming and inclusive for everyone to participate from the grassroots up is still a work in progress. Dalton says that she’s always disheartened when she hears of young girls starting a sport but then quitting it.

“It might be that they’re given a uniform that doesn’t fit them because it’s a hand me down from the men’s team,” Dalton says.

“It might be that they’re conscious of their body in a tight uniform or worried about having their period in a pair of white shorts.” Dr Adele Pavlidis, associate professor in sociology at Griffith University in Queensland, says there’s “a huge dropoff rate” at around 14 years of age for young people in sport.

“It’s boys, too, but mostly girls and we know from research that the reasons are complicated, with some studies noting that body image and shame form part of those barriers. If we create a more inclusive culture, it’s helping boys, men and nonbinary people as well.”

Over the past year, following revelatory research by Hanlon and her team at Victoria University about women’s opinions on their sports uniforms nationally and internationally, AFLW and Cricket Victoria no longer require players to wear white shorts or pants, while Swimming Australia, Gymnastics Australia and Netball Australia, have all introduced flexible uniforms.

“These changes show that the leadership in these sports care about women and girls feeling comfortable,” says Hanlon.

Leadership and governance

Governance is critical, too. After being a player, Kane became a coach and then administrator. In 2015, she began working with the North Melbourne Football Club as they bid for one of the licences to have a women’s team in the inaugural AFLW competition. She experienced first-hand all the discussions about how facilities would have to be expanded to provide enough change rooms and toilets for girls.

Dalton is also part of the Minerva Network, which partners female athletes with C-suite women to mentor them, while “creating networks, as well as training and equipping women to join boards and lead sporting organisations.”

Hanlon says that while Australia has seen a lot of progress for women’s sports, there is more to be done. “We’ve had a lot of game-changing situations occur for women as players last year, but let’s bring on more opportunities for women as leaders this year – as coaches, umpires, officials, managers or board members. We need to make leadership spaces more family friendly.”

The experience of other women, such as sailor Nina Curtis, who had a baby in May 2023 and is soon to compete in the Women’s America’s Cup event in Spain, is inspiring for women whichever sport they play, says yachtswoman Tarnawski. “You can push yourself, grow professionally in the sport and you can have a family too.”

Read more from the magazine…

Girls Don’t Change the World

A special International Women’s Day magazine by Pymble Ladies’ College, in association with the Financial Review.

This special publication features topical articles written by independent journalists about women’s achievements and challenges in business, law, sport, science, technology and education whilst highlighting the pace of change toward gender equality in Australia.